You might think you are a great hopper, but that is because you are never on the same leg hopping forward sequentially. Running is hopping off one good leg, potentially onto another that is just a little less optimal, then back onto a better leg, never fully appreciating a potential asymmetry.

If you are not assessing your client's hop ability you might be missing some very valuable information. The trouble will be, determining what the deficit is. Telling them they merely have to hop more on the perceived-deficit side is not solving the problem. More does not equal better (unless one is referring to ice cream).

Today, we are in the podcast studio and we will briefly be talking again about the importance of assessing your client's hop ability. Do they have the skill, endurance and strength to hop well, and hop symmetrically? After all, running is a hopping skill, it is a long jump hop forward in the sagittal plane, followed by an airborne float phase, and an abrupt landing onto the next limb, it is a long jump hop one after the other. If you cannot hop competently, you are at risk.

Skill: Do you have the skill to hop symmetrically ? When you do 15 fast hops forward do the legs feel the same side to side in terms of coordination? or is your foot all over the place "exploring for stability"? Does your knee swim inward, does your hip drift a little into the frontal plane, do you drop the swing leg pelvis ?

Endurance: Can you do it 15 -20 times or more, how about 50? After all, you are about to do a 5mile run (or more !). If you fatigue in any of the components on one leg, your hops are not the same. Get ready for compensation adaptations. So, when you feel something going "funky" wrong in a long run, what do you do? Do you stop, walk and recover or do you keep going ? Many of us are good at ignoring the "blinking check engine light". There is nothing wrong will walking for a bit and giving some fatigued tissue a little time to recover before you start into your run again. We believe many injuries could be avoided if we could get past our "mental moron" issues as runners.

Strength: can you protect the joints and planes from compromise, drift, rotation etc ?

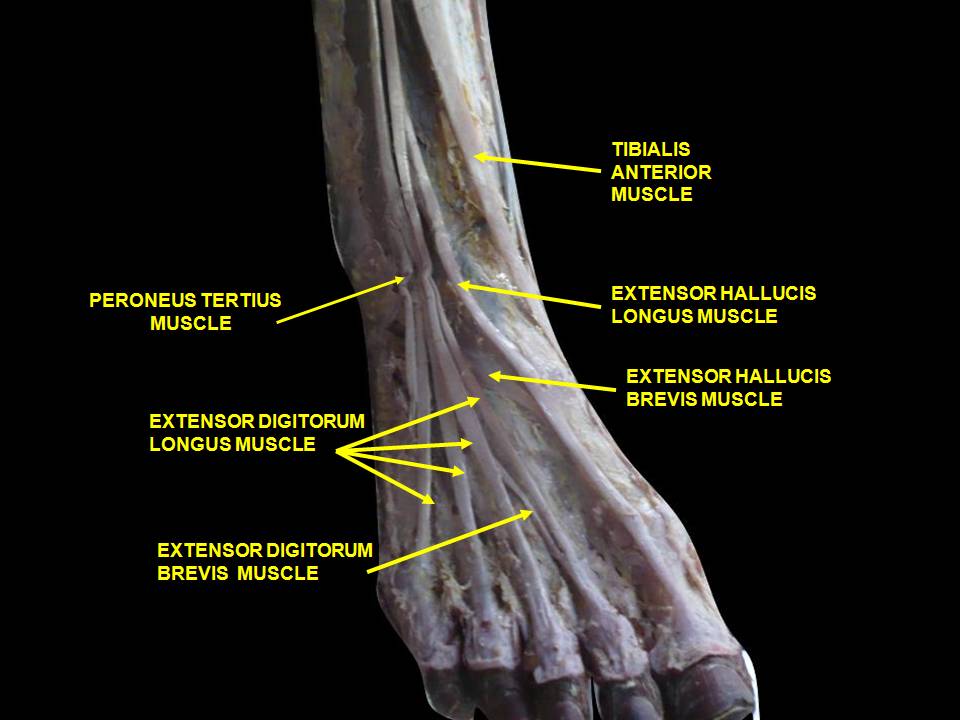

Hopping comprises: proprio, forefoot take off and loading, ankle rocker, a competent tibialis posterior, peroneal group, and achilles-calf complex, knee flexion dampening ability, hip flexion and others . . .

you must be able to stabilize the frontal plane

you must be able to dampen rotational loads

you must be able to keep the knee sagittal

you must control the rate of pronation

you must be able to cyclically convert the foot from flexible to rigid and back again, almost immediately

Just some things to think about before your long run this weekend. We will follow up this post with a long form discussion on an upcoming podcast. We hope you will tune in.

"It is concluded that the fatiguing exercise protocol combined with single-leg hop testing was a reliable method for investigating functional performance under fatigued test conditions. Further, subjects utilized an adapted hop strategy, which employed less hip and knee flexion and generated powers for the knee and ankle joints during take-off, and less hip joint moments during landing under fatigued conditions. The large negative power values observed at the knee joint during the landing phase of the single-leg hop, during which the quadriceps muscle activates eccentrically, indicate that not only hop distance but also the ability to perform successful landings should be investigated when assessing dynamic knee function.

Single-leg hop testing following fatiguing exercise: reliability and biomechanical analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2006 Apr;16(2):111-20 Augustsson J1, Thomeé R, Lindén C, Folkesson M, Tranberg R, Karlsson J. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16533349