One way compensations develop

We have all had injuries; some acute some chronic. Often times injuries result in damage to the joint or articulation; when the ligament surrounding a joint becomes injured we call this a “sprain”.

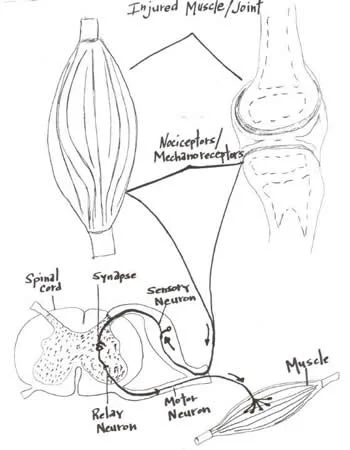

Joints are blessed with four types of mechanoreceptors. We have covered this in many other posts (see here and here). These mechanoreceptors apprise the central nervous system of the position (proprioception or kinesthesis) of that body part or joint via the dorsal column system or spinocerebellar tracts. Damage to these receptors can result in a mismatch or inaccuracy of information to the central nervous system (CNS). This can often result in further injury or a new compensation pattern.

Joints have another protective mechanism called arthrogenic inhibition (see diagram above). This protective reflex turns off the muscles which cross the joint. This was described in a few great paper by Iles and Stokes in the late 80’s an early 90’s (vide infra). Not only are the muscles inhibited, but it can also lead to muscle wasting; there does not need to be pain and a small joint effusion can cause the reflex to occur.

If the muscles are inhibited and cannot provide appropriate afferent (sensory) and efferent (motor) information to the CNS, your brain makes other arrangements to have the movement occur, often recruiting muscles that may not be the best choice for the job. We call this a “compensation” or “compensation pattern”. An example would be that if the glute max is inhibited (a 2 joint muscle, with a larger attachment to the IT band and a smaller to the gluteal tuberosity; it is a hip extender, external rotator and adductor of the thigh), you may use your lumbar erectors (multi joint muscles; extensors and lateral rotators of the lumbar spine) or hamstrings (2 joint muscles; hip extenders, knee flexors, internal and external rotators of the thigh) to extend the hip on that side, resulting in aberrant mechanics often observable in gait, which may manifest itself as a shortened step length, increased vertical displacement of the pelvis, lateral shift of the pelvis or increase in step height, just to name a few. Keep this up for a while and the new “pattern” becomes ingrained in the CNS and that becomes your new default for that motion.

Now to fix the problem, you not only need to reactivate the muscle, but you need to retrain the activity. Alas, the importance of doing a thorough exam and thorough rehab to fix the problem.

Often times, the fix is much more involved than figuring out what the problem is (or was). Take your time and do a good job. Your clients and patients will appreciate it!

Ivo and Shawn, the gait guysYoung A, Stokes M, Iles JF : Effects of joint pathology on muscle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Jun;(219):21-7

Iles JF, Stokes M, Young A.: Reflex actions of knee joint afferents during contraction of the human quadriceps. Clin Physiol. 1990 Sep;10(5):489-500.